Where do fish call home?

RTE reported this week, that the Irish fishing industry could potentially see a huge slump in some fish quotas if the UK prevails in its ambitions in the Brexit fisheries negotiations. The numbers are staggering – some Irish quotas could drop by >60%. The method of sharing out quotas, has evolved since the 1970s. The EU has said it will not conclude a free trade agreement (FTA) with the UK unless there is a separate agreement which grants continued access for European fleets to UK waters. Britain insists that as it is leaving the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) it will resume control over the quotas in its waters. Listening to a representative from the fishing community in Killybegs, Co. Donegal yesterday morning, who referred to the fact that fish move about – and that climate change is impacting this movement. So where numbers may be high in some locations at one time, this can change and fish do not experience the same boundaries – as we create. These climate related factors must be taken into account when developing the policy that affects both fish stocks and livelihoods.

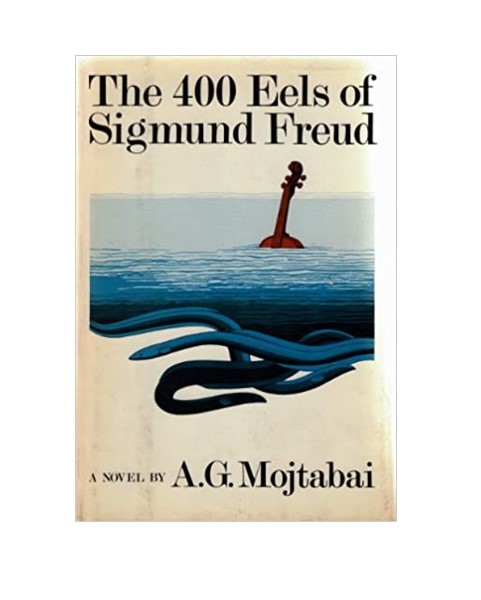

Climate change may be severely impacting the silver eel, a subject of long term study at the Marine Institute (MI) research station in Burrishool, Newport, Co. May. The scientists there have been studying silver eel since 1959. The MI team have full trapping facilities for over 40 years, giving the longest time series for mature European Eel – a really unique dataset on silver eel downstream migration. These migration patterns are really important and have interested researchers over the years. In 1876 Sigmund Freud[1] wanted to be the first person to find what men of science had been seeking for thousands of years: the testicles of an eel. The question that has challenged scientists back to Aristotle is: Where do eels come from? European eels, Anguilla anguilla, were widely eaten. Eels were unaccountable, writes the Swedish journalist Patrick Svensson.[2] In his guide to the eel – Svensson says that people caught eels in little streams, rivers, lakes, the sea. Pliny the Elder, [3]whom I often like to consult, thought that new eels developed when old eels rubbed away parts of their bodies on rocks. But, the eel is a creature of alteration, four distinct phases: a tiny gossamer larva with huge eyes; a shimmering glass eel, (an elver); a yellow-brown eel; and, finally, the silver eel. With the last change, the eel’s stomach dissolves—it travels thousands of kilometres on fat reserves—and its reproductive organs finally develop. In the eels of Europe, no one could find those organs because they did not yet exist – explaining why Freud couldn’t find what he was looking for. Danish researcher, Johannes Schmidt,[4] traced the European eel, Anguilla Anguilla to the Sargasso Sea. While most fish do not have such incredibly interesting lifecycles, that have challenged scientists and philosophers over the years – fishing policy cannot be developed without considering the shared waters, movement of fish and the impact of changing climate on future stocks.

[1] In 1876 Freud works in the Institute of Comparative Anatomy and receives a research scholarship to work at the Laboratory for Marine Zoology in Trieste. There he studies the sexual organs of eels and produced his first publication on this subject but is not happy about the inconclusive results.

[2] Patrick Svensson, (2020) The Book of Eels, Our Enduring Fascination with the Most Mysterious Creature in the Natural World: Harper Collins.

[3] PLINY THE ELDER, Natural History

[4] SCHMIDT, J. Oceanographical Expedition of the Dana, 1928–1930. Nature 127, 444–446 (1931). https://doi.org/10.1038/127444a0

Recent Comments