Day Zero

“Day Zero” is a phrase being used in the news more and more in relation to water. Although, it sounds like a title of a science fiction movie, unfortunately it is a relatively new reality facing all societies.

The first time I read about it was in 2019 when successive droughts and extra water needed to fight intense bushfires in Australia caused an unprecedented water shortage, with numerous regions facing the prospect of the taps running out within a matter of months.

Day Zero, as it’s called, marks the start of water rationing and the day residential taps are turned off – literally – with large numbers of households and businesses having to go to local collection sites to fetch water.

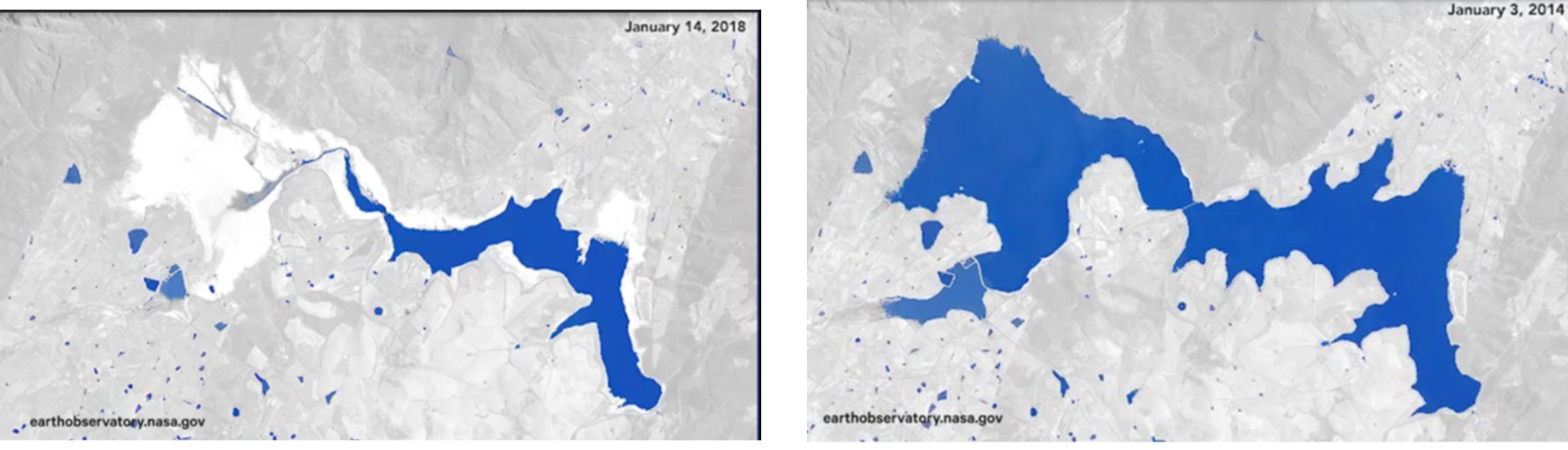

If you lived in Cape Town in 2017, you will be very familiar with this term. With a population of 4 million, Cape Town saw a declining drop in its rainfall from 2015. Then in 2017, reservoir levels reached an all-time low and officials came to the point of informing their citizens that municipal water supplies would largely be switched off and residents would have to queue for their daily ration of water, making the City of Cape Town the first major city in the world to potentially run out of water. [1].

The City of Cape Town implemented significant water restrictions in a bid to curb water usage, and succeeded in reducing its daily water usage by more than half to around 500 million litres (130,000,000 US gal) per day in March 2018. The fall in water usage, combined with strong rains in June 2018, led dam levels to steadily increase, and for the City to continually postpone its estimate for “Day 0”. In September 2018, with dam levels close to 70 percent, the city began easing water restrictions, indicating that the worst of the water crisis was over. [1]

The impact of the water crisis had severe economic and public health impacts on Cape Town. Tragically, one of adverse impacts was that over 37,000 people lost their jobs pushing them below the poverty line.

New data from WRI’s Aqueduct tools reveal that 17 countries – home to one-quarter of the world’s population—face “extremely high” levels of baseline water stress, where irrigated agriculture, industries and municipalities withdraw more than 80% of their available supply on average every year. Such a narrow gap between supply and demand leaves countries vulnerable to fluctuations like droughts or increased water withdrawals, which is why we’re seeing more and more communities facing their own “Day Zero”. [2]

By Ruth Clinton

Water Innovation Officer

Recent Comments